Key 2025 Trends and What’s Ahead

ScienceSoft’s healthcare consulting and analytics teams regularly track how technology and economics reshape care delivery. In 2025, we reviewed how the US hospital system has evolved over the past two decades. The facts speak for themselves: inpatient admissions have steadily fallen, while outpatient encounters have grown and diversified. Hospital employment is climbing despite fewer beds, underscoring the shift from volume to complexity. Taken together, these signals point toward hospitals evolving into service networks that extend well beyond the ward. We anticipate that this trend will persist in the upcoming years, accompanied by a growing emphasis on preventive health services.

From Inpatient Past to Outpatient Future

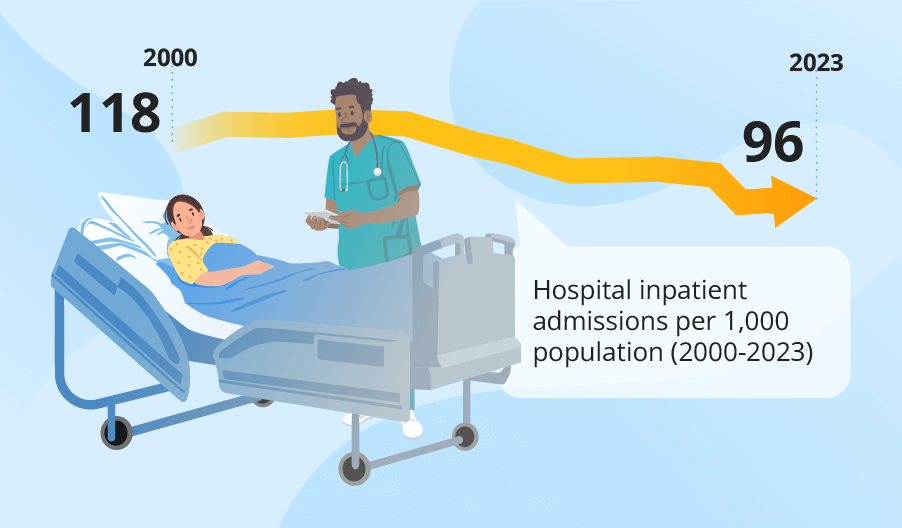

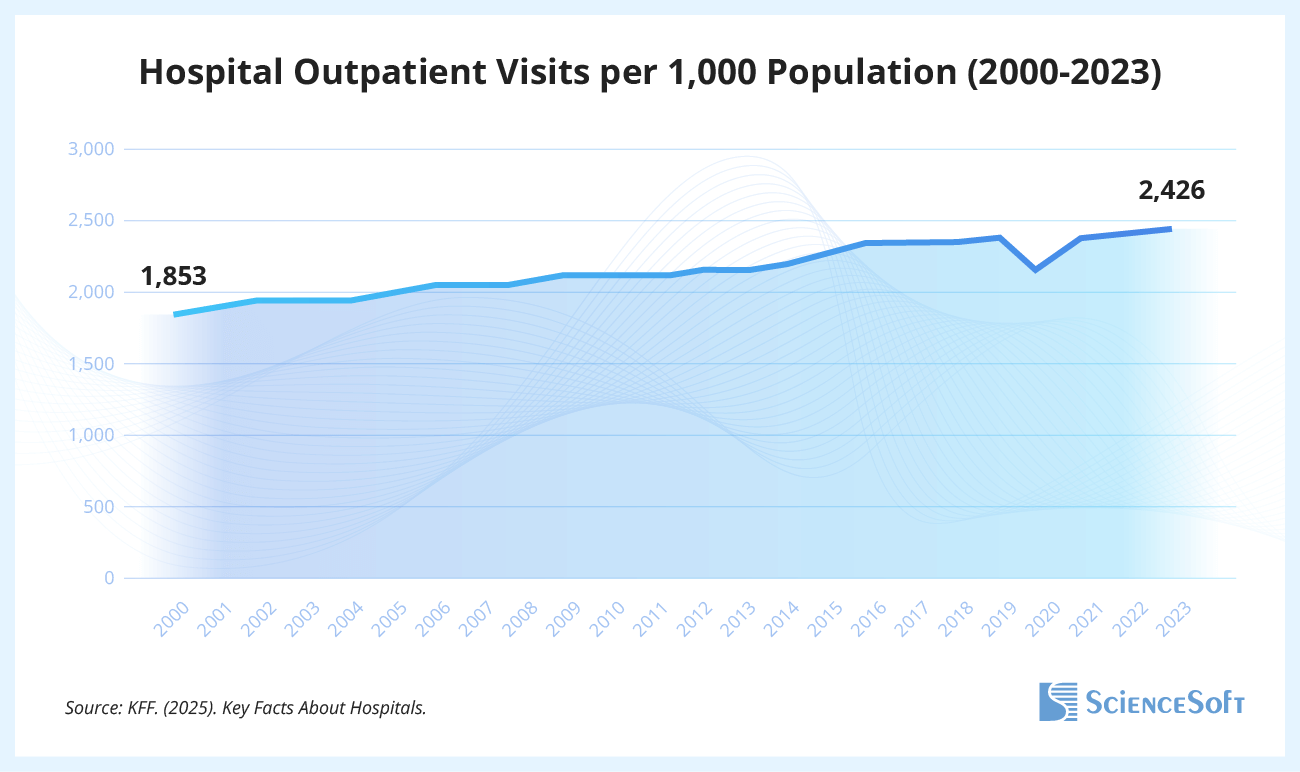

Two decades ago, inpatient care was the unquestioned backbone of hospital operations. Today, the numbers tell a different story: medical care is moving outside of the hospital walls. Between 2000 and 2023, inpatient admissions dropped by nearly 19%, while outpatient visits surged by 31% (KFF).

The infrastructure has followed suit: the number of staffed hospital beds per 1,000 people fell by 23% since 1999. Even with this reduction, hospitals are not running at full tilt: in 2022, average occupancy in general acute care hovered around 66%, leaving one in three beds empty on any given day. The average length of stay has also steadily declined (from 5.6 days in 1994 to 5.2 days in 2021 (HCUP)), reflecting the advances in modern-day patient care. Fewer nights in the hospital are needed because more care can safely be delivered through remote monitoring, same-day procedures, and virtual follow-ups.

The economic and clinical logic aligns. Overnight hospitalizations are the most expensive form of care, carrying heavy infrastructure and staffing costs. Payers and providers alike are incentivized to reduce unnecessary inpatient days, and advances in technology make that possible. In 2025, US hospitals are handling more encounters with fewer beds, because a growing share of care now happens before, after, and outside an overnight stay.

But this isn’t only a cost story. Shorter inpatient stays and well-established outpatient pathways mean less disruption to daily life and often lower exposure to hospital-acquired infections. At the same time, the trend raises questions of preparedness: if beds are consistently trimmed and admissions keep dropping, hospitals may struggle to flex up capacity in public health emergencies, when surges of inpatient demand return overnight. We already saw an example during the COVID-19 outbreaks. Emergency department visits spiked from about 130 million in 2018 to 151 million in 2019, and again to 155 million in 2022, reflecting how quickly demand can rebound and test limited capacity.

Hospitals Become Complex Service Networks

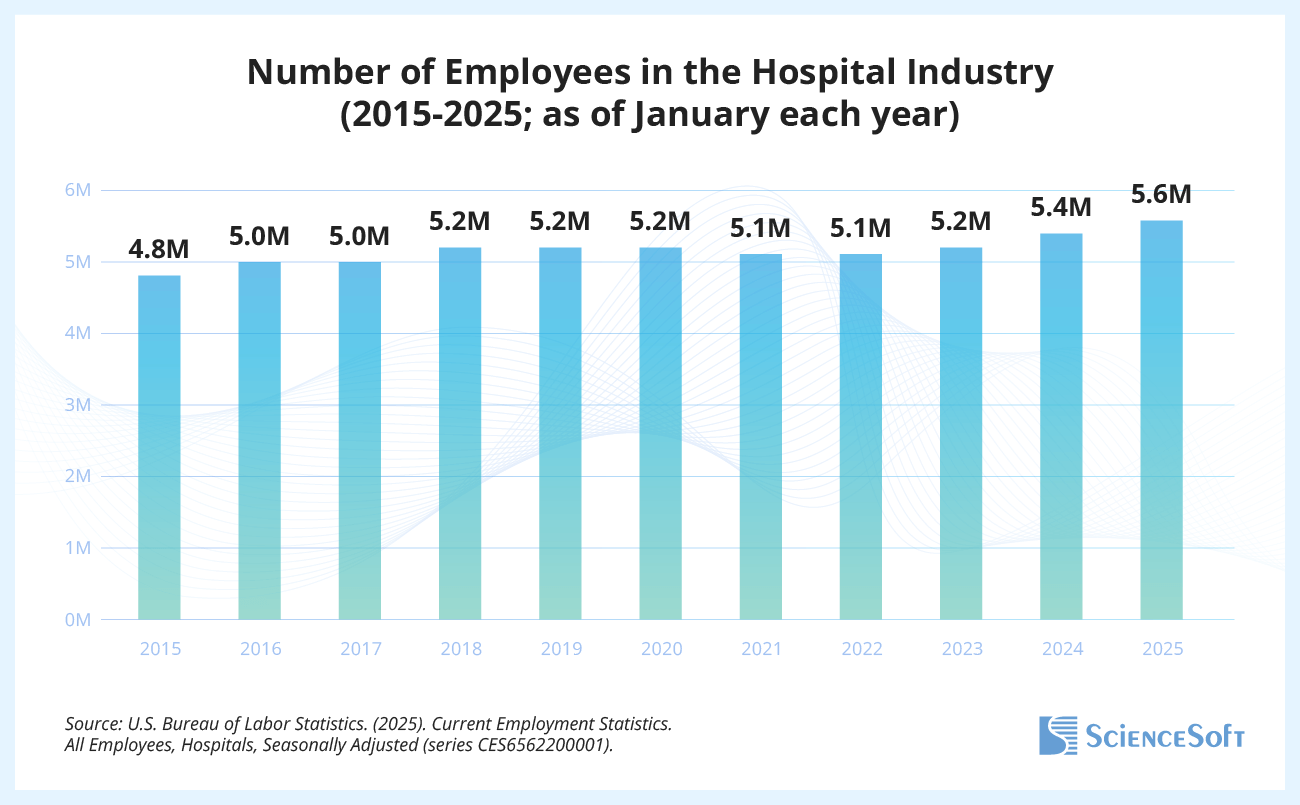

As of early 2025, US hospitals employ about 5.6 million people, a steady climb after the pandemic dip and a clear signal that demand for hospital-based labor is not tied solely to the number of occupied beds. When COVID-19 subsided, hospitals faced a massive backlog of postponed care. Meeting that surge meant hiring across the board: more clinical staff and technicians on the front lines, but also new support personnel to keep operations moving.

At the same time, the number of hospitals has stayed broadly stable in recent years, with the latest data showing 6,093 facilities in 2023, compared with 6,146 just five years earlier (AHA). In other words, it’s the hospital itself that’s expanding. Digital health initiatives require IT specialists, outpatient growth demands care coordinators, and more complex patient needs call for a broader range of medical professionals. The result is a workforce that is not only larger but also more diversified than before. In 2025, labor stands as hospitals’ single most significant expense and a central factor in whether providers can remain financially sustainable.

As of 2023, the U.S. has 6,093 hospitals, including 5,112 community hospitals — of which 2,978 are nonprofit, 1,214 for-profit, and 920 government-owned. Among community hospitals, general medical and surgical facilities dominate, accounting for 4,235 hospitals (83%). They are followed by rehabilitation hospitals (353, or 7%), acute long-term care hospitals (262, or 5%), children’s hospitals (82, or 1.6%), and cancer hospitals (15, or less than 1%), with another 165 hospitals (3%) falling into other specialized categories.

Revenue is also growing. Between 1998 and 2022, hospital revenues more than tripled, going from $391 billion to $1,369 billion. Part of this growth comes from expanding service lines, including remote procedures, early diagnostics, and preventive programs. Medical institutions are expanding horizontally, becoming more like consolidated hubs for diverse services.

Consolidation is a factor in and of itself. Today, the lone independent hospital is becoming a rarity. As of 2023, nearly seven in ten community hospitals were part of a hospital system. Scale brings negotiating power with insurers, shared infrastructure for digital health and procurement, and a buffer against margin pressures. For patients, this often means a recognizable system brand across multiple care sites, though it can reduce local competition and keep prices high.

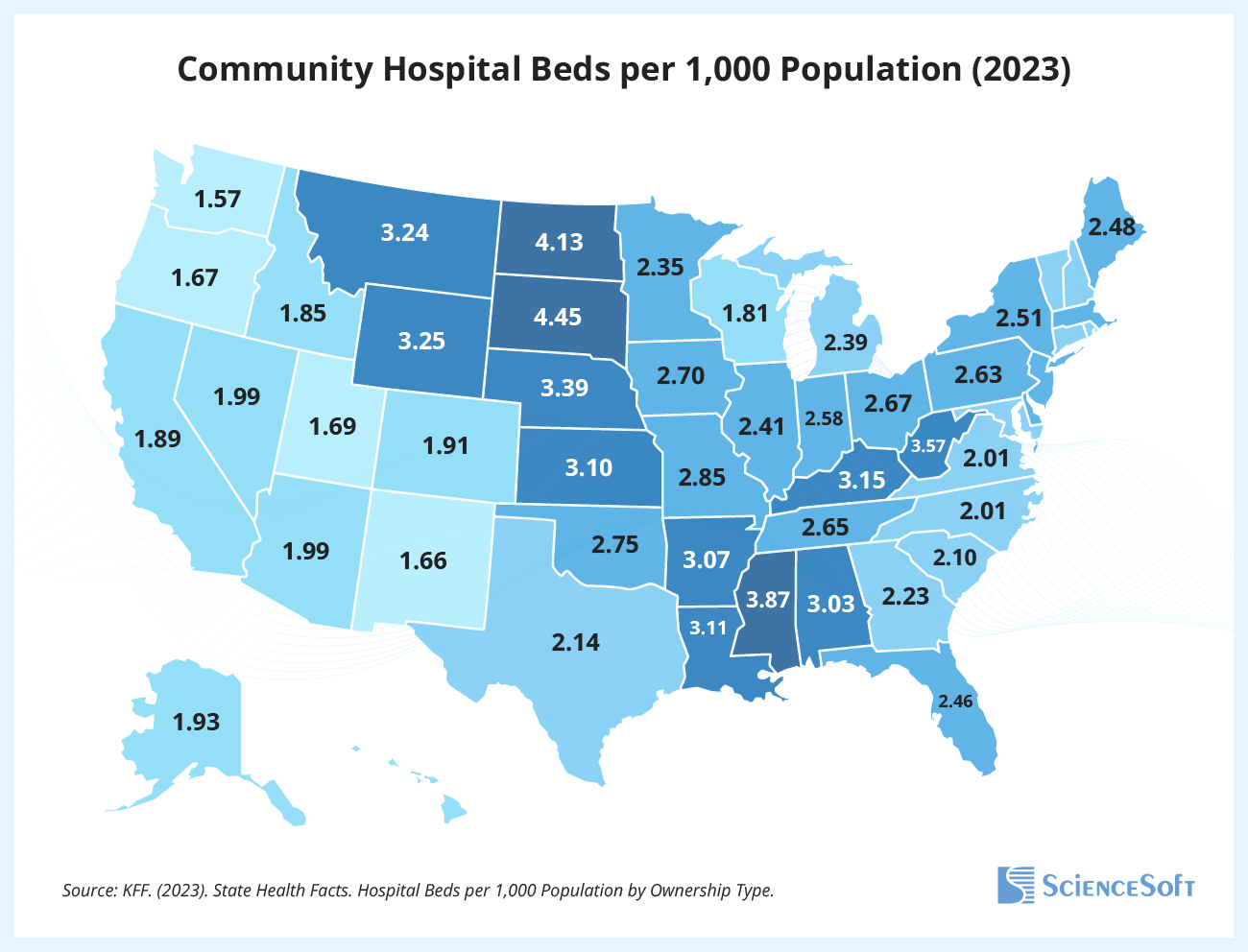

Fewer Beds Everywhere, But Some States Are Barely Covered

Every state has fewer beds than a generation ago. According to the National Center for Health Statistics and the Kaiser Family Foundation, from 1980 to 2023, all 50 states recorded declines in community hospital beds. The sharpest decline occurred in Wisconsin, where bed numbers fell by a factor of 2.5. The latest available data shows that the District of Columbia now leads with 4.87 beds per 1,000 people, while Washington state has only 1.57 (KFF).

The number of hospitals mirrors this uneven picture. Texas tops the list with 498 hospitals, followed by California, Florida, and Ohio, while smaller or more rural states such as Delaware, Vermont, and Alaska each have fewer than 20 (AHA). Regions with fewer hospitals per capita often overlap with those with the lowest bed density, leaving many communities thinly covered even before accounting for distance or specialization.

At large, every state has seen its bed supply shrink since 1980, as inpatient care steadily gave way to outpatient alternatives. But not all states have been affected equally. Some regions now face much tighter hospital capacity, which becomes especially problematic when a crisis sends a sudden wave of patients their way.

A Growing Access Crisis in Rural America

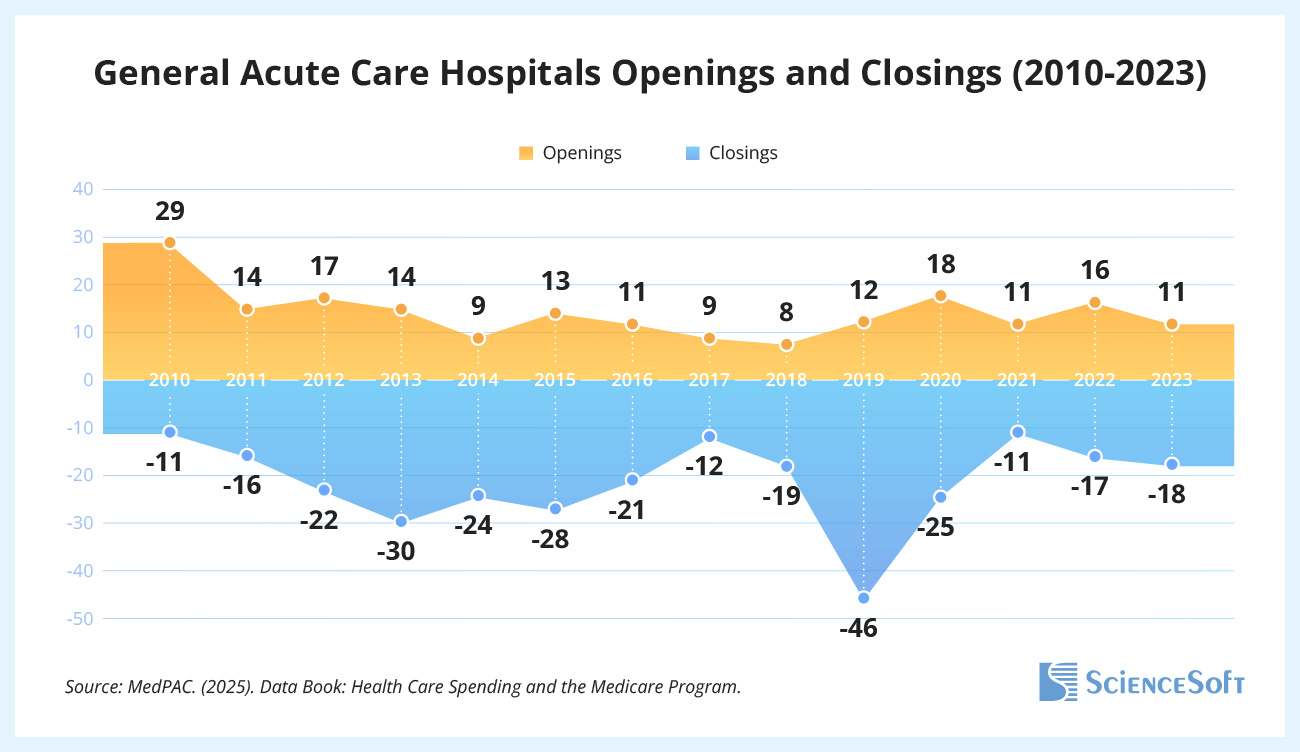

While the national hospital system grows in size and revenue, many communities are left with shrinking accessibility. Rural hospitals are closing faster than they can be replaced. From 2010 to 2023, the US saw 108 more closures than openings of general acute care hospitals. Each year, between 11 and 46 hospitals shut their doors, with a particularly severe impact in rural areas. Rural hospitals make up only about a third of all US facilities, so every closure hits hard. In 2025, rural hospitals continue to operate on thinner margins, leaving many communities at risk of losing access to essential services. Average patient-service and total margins in rural hospitals lag well behind their urban counterparts. Almost nine out of ten rural community hospitals are nonprofit or government-owned, while in urban areas, only about two-thirds fall into those categories (KFF). Mission-driven by design, rural hospitals remain vital safety nets — but financially fragile ones.

The consequences are immediate and ongoing. Patients face longer travel times for emergency care, ambulance services are stretched thinner, and jobs tied to the hospital disappear, hurting local economies. Closures also reduce local access to maternity wards, trauma units, and timely diagnostics, which widens the gaps in essential services for rural populations.

The Barbell Effect: Tiny and Mega Hospitals Thrive

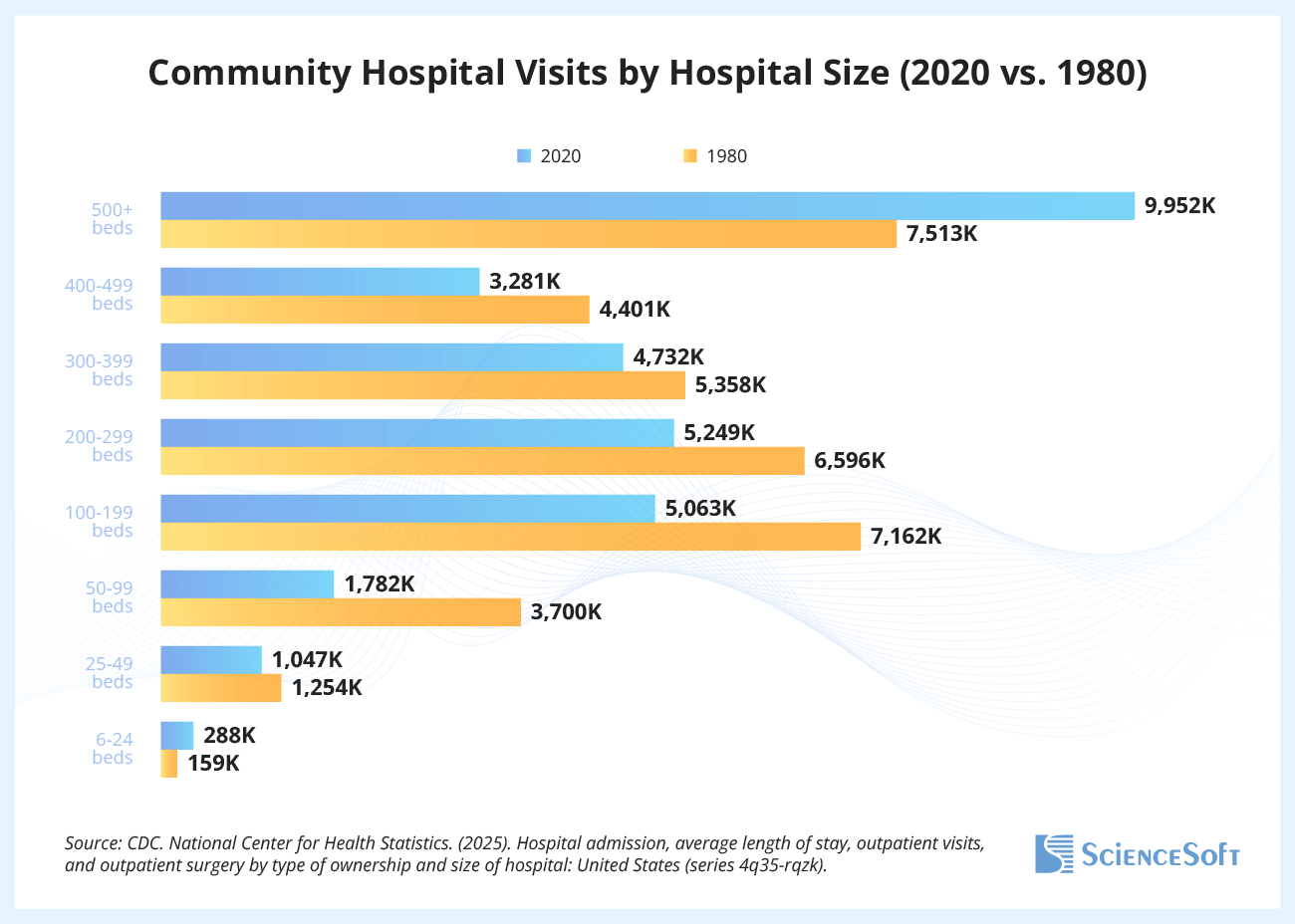

The demand has long been consolidating at the extremes. Over the past four decades, the smallest hospitals (6–24 beds) and the largest hospitals (500+ beds) have both seen admissions rise, while mid-sized facilities lost ground.

This breakdown reflects diverging roles. Very small hospitals — often in rural areas or specialized niches — continue to serve as vital community anchors, providing essential access where larger facilities are impractical. On the other hand, mega-hospitals are expanding as regional hubs for highly complex procedures, advanced technology, and specialist teams.

The middle is squeezed. Hospitals with a few hundred beds increasingly face the worst of both worlds: too large to be lean community providers, but too small to compete with the scale, technology, and negotiating power of major academic centers and system flagships.

Out-of-Pocket Burden Grows

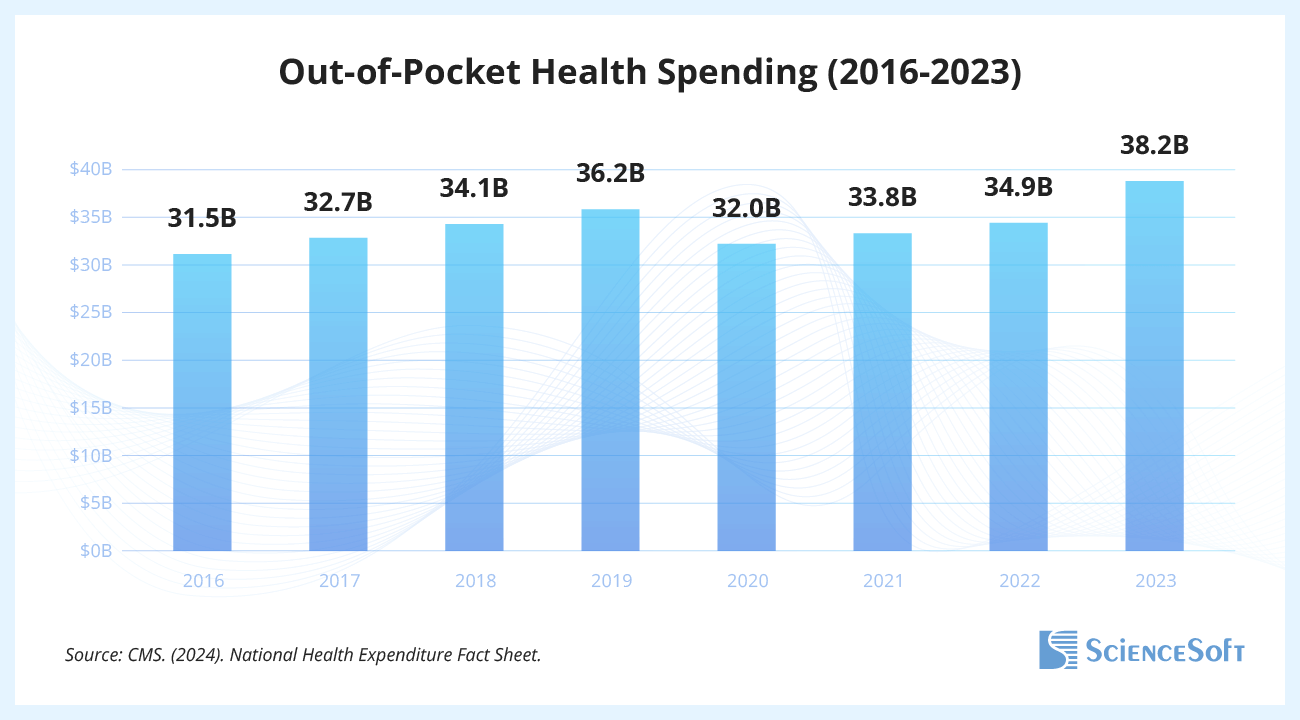

For patients, these structural shifts intersect with another pressing reality: the rising cost of care. In 2025, hospitals, insurers, and policymakers are caught in a cycle: higher costs fuel higher patient contributions, which in turn influence utilization patterns and, ultimately, health outcomes.

According to the latest available stats, half of all patients with at least one overnight stay paid $1,000 or more out of pocket in 2022, on top of premiums, deductibles, and other medical expenses. Total out-of-pocket spending on hospital services had climbed more than 20% in just 7 years, reaching $38.2 billion in 2023.

At the same time, hospital admissions are gradually declining (from about 36 million in 1975 to 34 million in 2023, according to the National Center for Health Statistics), suggesting that fewer Americans are turning up for care. Admissions fall, while costs are rising; coincidence? Perhaps not. When a single hospital visit can translate into thousands of dollars in out-of-pocket bills, patients look for alternatives, sometimes abandoning treatment altogether.

All of this can lead to delayed care, skipped follow-up appointments, and mounting medical debt for households. Surveys indicate that even modest unexpected bills — often under $1,000 — cause financial distress for many families. With hospital stays now regularly exceeding that threshold, many patients face difficult trade-offs about when and where to seek care.

Hospitals Still Struggle to Share Data

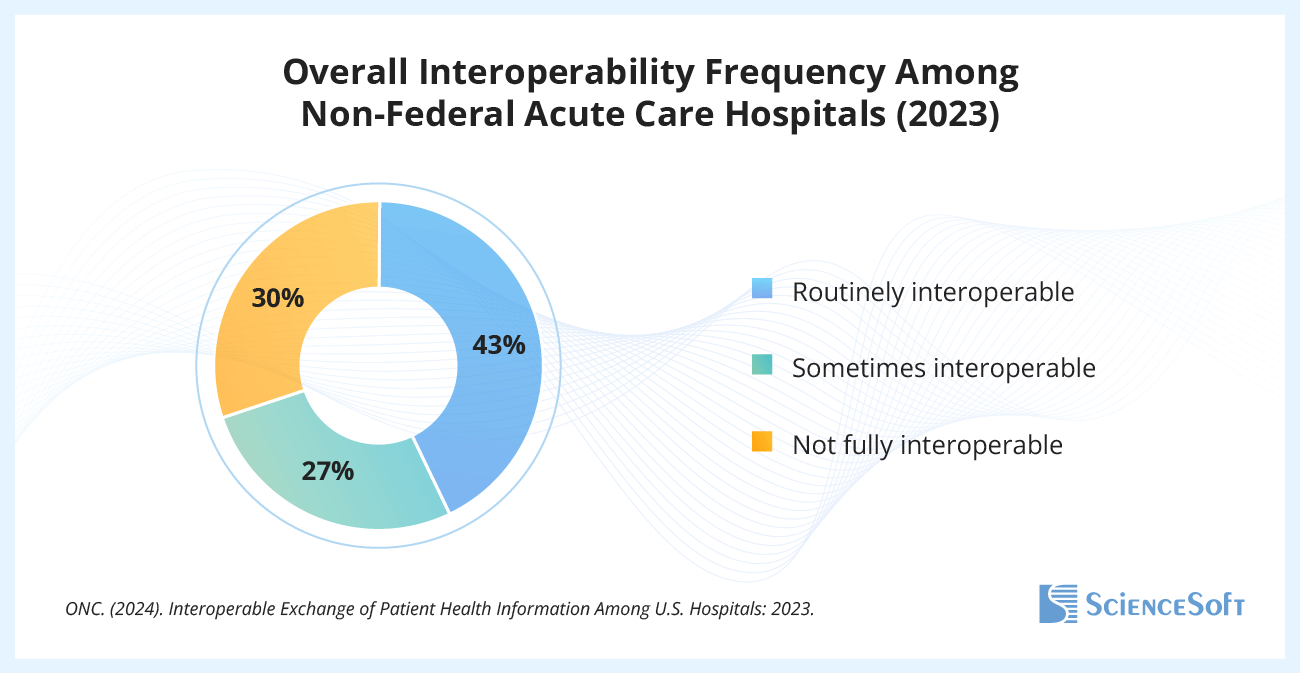

In 2025, interoperability remains one of the most pressing operational gaps in a system that increasingly depends on continuity across settings. Despite massive investments in electronic health records, as of 2023, fewer than half of US non-federal acute care hospitals routinely exchanged patient data. The divide is sharpest for smaller, rural, and Critical Access facilities, while large, urban, and system-affiliated hospitals are more likely to share information across settings.

Interoperability in healthcare is the foundation for reducing duplicate tests, preventing medication errors, and ensuring continuity when patients move between providers. As hospitals expand into outpatient clinics, home care, and virtual services, the risk grows that a patient’s record fragments across systems. Hospitals are getting bigger as businesses, but without interoperable data, the patient’s story still breaks at the handoff.

The federal government has begun to raise the stakes. The Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement (TEFCA) now provides the first nationwide infrastructure for secure data exchange, and regulators are enforcing information-blocking penalties to make sure providers and vendors comply. In 2025, interoperability is getting further away from being optional. Hospitals that fail to close the gap risk being left behind in a healthcare system built on continuity.

Want to explore these insights in greater depth? Connect with ScienceSoft’s experts to discuss how these trends translate into practical strategies for healthcare organizations.