A Weird Summer of AI Deals

Midyear 2025 has been the first time that AI has truly affected the daily work on this author’s desk. Prior to this, we spent a lot of time periodically researching, reviewing, prognosticating, writing, and inquiring – but it was about possible futures, not the effect in the present. Not so today: the summer of 2025 has seen AI take effect day-to-day, and even hour-to-hour.

Weirdly Fast AI-SaaS Growth

Multiple times this summer, we’ve seen AI-first SaaS companies looking for financing and posting up astounding growth rates. We’re talking about rates of 50-100% per month in what they claim as Monthly Recurring Revenue (MRR). (Obviously, these have been relatively short histories and small starting points, as a 100% monthly growth rate compounds to an implausible 409,500% annual rate.)

We’ve also observed some similarly astounding numbers in press reports regarding public companies. Wix publicly bragged recently that their acquisition of AI-webapp generator Base44 for a “mere” $80 million is now resulting in $1 million in new MRR bookings per month. At a modest 5x ARR, that would mean an acquisition that paid for itself in…five weeks.

And yet, somehow, despite these absolutely phenomenal results, many such companies are still looking to borrow fairly modest credit facilities, or being heralded in mid-tier public company press releases, instead of going IPO themselves. I am suspicious that much of today’s AI revenue growth is misleading or fake in some way.

And to qualify these observations, we are considering here only the very high growth outliers among B2B, recurring-revenue AI offerings: what we’re beginning to call “Subscription-AI-and-Software” (redefining SaaS for 2025+). While there are certain liberties being taken with SaaS metrics even in traditional SaaS companies, this piece will focus on the AI hype cycle.

Misleading: In cases where the hypergrowth is real (not fraud), it may still not be “Recurring Revenue” in the way the SaaS industry has come to understand it. For reasons I’ll get into below, you can’t just consider many of these AI tooling users, like normal B2B SaaS users, to be ordinary, commercial, and retained, that is: people 1. who do some kind of normal ongoing business process that benefits from the software (ordinary course of business), 2. who get more value from the software than they pay for it (conducting a normal commercial trade), and 3. who will continue using it (retention). These not-normal users I am calling weird.

Fake: I think in some cases, founders/management teams are juicing the numbers to raise capital. One fake approach is outright fraud (but I don’t think it’s mainly that)1. A gentler way that it might be fake, with management collusion, is by having super lax standards of trade credit/payment terms, thus reporting as “recurring” revenue that there is little evidence it will actually recur. These not-normal users I am calling fake.

Weird Users of AI Will Try Everything Once

As a result of massive publicity, dazzling demos, and vaulting promises of productivity, budgets and curiosity have been turned loose so that a large fraction of business IT buyers (from individuals on up) are willing to try everything in a category at least once. I’ll illustrate this with perhaps the best use case for AI tooling, namely, coding co-pilots (including VSCode, Cursor, Claude Code, and a hundred other offerings like Base44).

There are around 2 million software developers, by the most liberal definition, in the US. At least half can be considered junior, and many work on systems so ancient or secret that current AI offerings are not an option. A good upper bound for the number of intermediate-to-senior-level devs working full-time in the US is 500,000.

Those 500k possible users cost their employers at least $100,000 annually. The current pro-level pricing of Claude Code, Base44, and most AI-as-a-service developer tools seems to be around $200/month in mid-2025. At that price, almost any expected productivity boost from AI would be worthwhile, priced at 2.4% of annual salary.

Therefore we should expect hundreds of thousands of devs to at least try almost every tool out there. Even if their employer doesn’t reimburse them, it’s absolutely a no-brainer. In fact, one public company generated a lot of PR by noisily claiming to have fired any developers who hadn’t tried such a tool yet.

But it’s almost equally clear that they won’t keep all the tools they try. Developers focus, at least serially, on a subset of technologies and “stacks,” and they will use the “toolchain” that provides the best mix of personal satisfaction, “fit” with the current job’s stack, and acceptability to management.

I fully expect that among this cohort you will see initial price insensitivity up to $500 a month or so, but you’ll also see 75% churn rates within the year. Organizations and individuals will be racing to try 2, 3, 4, or more of these offerings, and then will rapidly consolidate down to the 1 or 2 that best suit them.

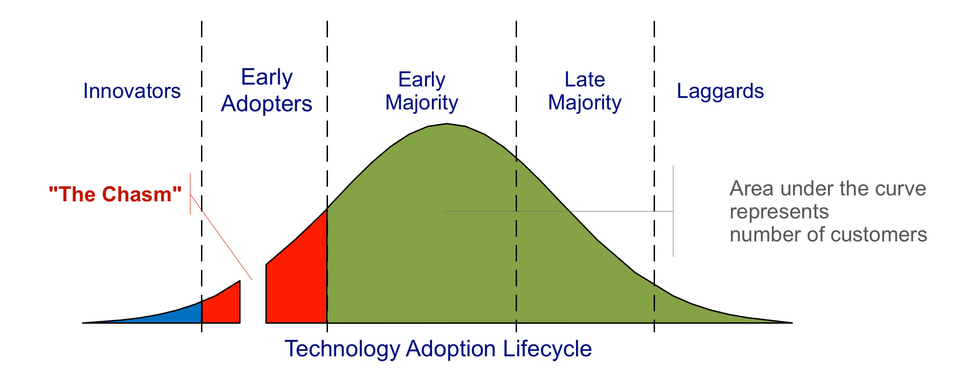

Since this will all be happening as the Early Majority (from Moore’s “Crossing the Chasm”) races to adopt, growth will remain high as the number of new try-outs outpaces churn:

Picture credit: Craig Chelius

But Gross Revenue Retention will be absolutely dismal as high churn equates to short customer lifecycles. Net Revenue Retention in comparison will look relatively good as individuals and organizations settle into their preferred solutions and become amenable to price increases (which are either happening or on the horizon, see e.g. VC-Funded AI Coming to a Close). But revenue retention for lightning-quick-adopted AI tooling – even in the arena of coding co-pilots, arguably the best product-market fit for AI capabilities today – will not be commensurable with the SaaS retention standards we’ve all come to observe over the past 15 years.

Shady Players Have Already Started Trying Everything

In every tech rapid adoption cycle, some of the first folks to exploit the new capabilities are from the seedier side of things. That would include all the way from outright fraudsters to, shall we say, “ethically unconstrained marketing professionals.” In other words, scammers and spammers are quick on the scene. These users or customers may exist, but it’s inappropriate to consider them to be at all like normal subscription revenue customers: numbers that are based on this kind of usage are closer to fake than merely misleading.

AI services, particularly of the “generative” type that most folks mean when they say “AI” in 2025, are often a perfect match for the needs of scammers and spammers. For example, they need to create lots of temporary but plausible websites, domains, email inboxes, etc. in order to run their rackets.

Even if these grey-hat customers pay their bills on time, their status as customers should be scrutinized. Self-regulation or government intervention will eventually come into play, and vendors could face liability in addition to the need to “fire” possibly large numbers of customers.

Furthermore, the attitudes toward rules and restrictions of these grey-hats means that they are disproportionately likely to be the low-margin, loophole-exploiting, troublesome users of any service they inhabit. As a concrete example, consider a service with free/cheap introductory pricing. The guys who want to use that service to automate sending spams or scams … will simply automate their way into cycling through the free accounts.

Shady users will also exploit weaknesses in trade credit. It is uncommon but not unheard of in B2B SaaS to let users sign up and ask to be invoiced … and that’s equivalent to a freebie in the mind of the grey-hat. They’ll take a month of usage, get the arrears bill on Net-30 terms, then take it out to 90 days overdue, all the while never intending to pay. Finally, 150 days after the signup, you shut them off, and take the bad debt writedown on what is eventually five months of “MRR”.

There’s another pattern we’ve observed this summer: not quite outright scammers, but low-effort derivative entrepreneurs who sign up for an AI-service, then turn around and white-label it behind one or more AI-generated sites or apps, often claiming that they have unique technology when it’s just a wrapper. These arbitrageurs are sort of the first derivative of the legit adoption wave, as they skim some profit from the less informed end-users, and we expect them to be a flash-in-the-pan, with poor retention characteristics.

AI-as-a-service vendors and their investors should be very wary of the grey-hats and low-effort B2B customers.

Beware the Black Hats

A step beyond the shady side of fake usage growth is the actual fraud, where more than just putting “lipstick on a pig,” a company wholly falsifies usage or revenue numbers. We are not convinced that this is a driving force behind AI growth observations, but it would be foolish to discount it. It does happen, as we are reminded just today with the sentencing of the numbers-cooking founder of “Frank.”

We hope that this kind of thing is far beyond the ethics of anyone who would read this. But over the years, many tech frauds have begun with accepting the grey area first during a period of hypergrowth, and then facing overwhelming pressure to keep up expectations. It’s best to stay far, far away from the grey zone.

The Super-Weird

Finally, there’s a tiny tail risk of some super-weird things going on: For example, it’s possible that AIs are beginning to use other AIs. This might be competitors gathering intelligence. It might also be quasi-legitimate chaining of tools. Or it might be runaway loops as yet unnoticed by hyper-funded AI players.2 My intuition is that this is the least likely to be part of any one hypergrowth story – but that we will eventually see some truly unanticipated things happening here, given the nature of AI itself.

How to Talk About Your AI Hypergrowth

We recommend that entrepreneurs lucky enough to catch the lightning in a bottle of AI-driven hypergrowth make very clear to their leadership teams, boards, and capital providers the distinction between more-or-less “normal” subscription revenue customers and those that are “weird” (or worse). Here are some concrete suggestions to stay on the bright side of the line:

- Consider “seasoned” MRR reporting. In a seasoning framework, a company determines a period (perhaps the end of a trial period, or an empirical length of time) or amount of usage that reasonably corresponds to a sustained, committed relationship.

- Analyze customer ROI. B2B SaaS companies historically create more value for the subscriber than they charge for. Indeed, an ROI calculation is usually part of an inside sales process, and sometimes part of customer success / quarterly business reviews. Customers for whom ROI isn’t clear are not, in aggregate, going to behave like B2B SaaS subscribers.

- Bring in the (accounting) cavalry. It used to be a rule of thumb that by $5 million ARR a company should have at least a fractional CFO, and by $10 million, a full-time CFO and an audit. The faster the company is hurtling toward these milestones, though, the earlier professional talent should be brought in to institute controls on contracting/POs, trade credit, and collections – even though these unsexy functions often get left by the wayside during hypergrowth excitement.

1 Although sort of everybody in the ecosystem has an incentive to have everybody else juke their stats so that everyone’s valuations go up, so there’s a real groupthink/bubble possibility.2 Similar strangeness has happened in the past, as when naive metrics like “hits” and “page views” started to get highly obscured by the rapid-onset effects of bots (inflating), caching (deflating), etc. in the early Web days.

![]()